Sluice is a radical four-day art event that questions the role of the contemporary art fair. Taking place during Frieze Week, Sluice acts as a refreshing counterbalance to the corporate manufactured glamour of the Frieze Art Fair. This year Sluice is located on the South Bank in London’s iconic Bargehouse building at Oxo Tower Wharf. Throughout the weekend there will be performances, screenings, talks and a collection of artist-run spaces and galleries exhibiting new and challenging work. Unlike Frieze, entry is free. Spiralbound will be at the Sluice Art Fair throughout, displaying our range of recently published books.

Spiralbound is a non-profit artists’ publishing project exploring the  influence of new digital technologies on the material presence of the book. Strongly supported by London gallery studio1.1. and existing as an offshoot of Susak Press, we work with artists and writers who want to use the book medium to experiment beyond, and challenge their usual practice. By subverting the capabilities of digital print on demand, the project’s aim is to publish book editions that remain uncompleted and in flux as we allow our authors the opportunity to re-shape and interfere with the book’s original version. Spiralbound is investigating how new digital technologies influence the way in which we read literary texts and how new digital influence is encouraging experimentation with the materiality of the book.

influence of new digital technologies on the material presence of the book. Strongly supported by London gallery studio1.1. and existing as an offshoot of Susak Press, we work with artists and writers who want to use the book medium to experiment beyond, and challenge their usual practice. By subverting the capabilities of digital print on demand, the project’s aim is to publish book editions that remain uncompleted and in flux as we allow our authors the opportunity to re-shape and interfere with the book’s original version. Spiralbound is investigating how new digital technologies influence the way in which we read literary texts and how new digital influence is encouraging experimentation with the materiality of the book.

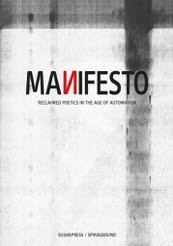

Spiralbound holds events throughout the year and at each event we launch new titles and also new editions of existing books. Our authors have the freedom to re-visit, edit and make a new edition of their book by adding or taking away image and text. As a result, the books Spiralbound produces reveal successive drafts and stages of an author’s work in progress. This allows the reader to collect and compare different versions of each book. By producing non-static content, Spiralbound is channeling performance and the immediacy of the live event into the book’s materiality whilst attempting to capture the flick and switch and pause and collect of internet- centered new digital media. For example in Manifesto (Daniel Devlin, John Hughes and Keran James), blurred images of unheralded literary and artistic figures of the twentieth and twenty-first century are uploaded and updated in each printing. These recycled and found images are juxtaposed with a collaborative group hacking and re-writing of an experimental text. Similarly, Skip I Am Far Above You (Keran James) unpacks and transforms internet spam into a piece of (in)coherent storytelling.

centered new digital media. For example in Manifesto (Daniel Devlin, John Hughes and Keran James), blurred images of unheralded literary and artistic figures of the twentieth and twenty-first century are uploaded and updated in each printing. These recycled and found images are juxtaposed with a collaborative group hacking and re-writing of an experimental text. Similarly, Skip I Am Far Above You (Keran James) unpacks and transforms internet spam into a piece of (in)coherent storytelling.

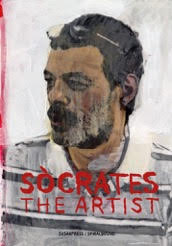

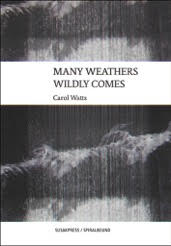

Books, like painting and sculpture, invite us to get our hands dirty  unlike the clinical touch and trace of digital surfaces. The materiality of new digital technologies, from the click of a mouse, to the thin peel of a protective iPad cover, to the buzz of a mobile on vibrate, are making contemporary writers and artists more conscious of the physical aesthetic of the book form. What connects the Spiralbound books is an engagement with the boundaries between fiction and reality. Both Socrates (Daniel Devlin) and Manifesto of A Tranny (Brian Dawn Chakley) capture live performance by combining text and video stills but it is unclear if these grainy images are depicting events that were stage managed, accidents or if they even took place. Biographies (Ghazal Mosadeq) plays with the recording and fabrication of fictional authors’ real life stories. Many Weathers Wildly Comes (Carol

unlike the clinical touch and trace of digital surfaces. The materiality of new digital technologies, from the click of a mouse, to the thin peel of a protective iPad cover, to the buzz of a mobile on vibrate, are making contemporary writers and artists more conscious of the physical aesthetic of the book form. What connects the Spiralbound books is an engagement with the boundaries between fiction and reality. Both Socrates (Daniel Devlin) and Manifesto of A Tranny (Brian Dawn Chakley) capture live performance by combining text and video stills but it is unclear if these grainy images are depicting events that were stage managed, accidents or if they even took place. Biographies (Ghazal Mosadeq) plays with the recording and fabrication of fictional authors’ real life stories. Many Weathers Wildly Comes (Carol  Watts) captures the practicality of an everyday walk yet is recorded through the blurred snapshots of a London dreamscape. Lamping Out The Trains part 1 (The RMT Jubilee South Branch Audio and Film Collective) combines oral recollections with fragments of radical London literature addressing themes of nostalgia, trauma and left-wing melancholia through a manipulation of found audio, film and text. The Glass Slipper (Athanasia Hughes) is a futuristic satire on consumerism and fashion and our increasing dependency on technology, yet the story is told through a relationship with a hologram.

Watts) captures the practicality of an everyday walk yet is recorded through the blurred snapshots of a London dreamscape. Lamping Out The Trains part 1 (The RMT Jubilee South Branch Audio and Film Collective) combines oral recollections with fragments of radical London literature addressing themes of nostalgia, trauma and left-wing melancholia through a manipulation of found audio, film and text. The Glass Slipper (Athanasia Hughes) is a futuristic satire on consumerism and fashion and our increasing dependency on technology, yet the story is told through a relationship with a hologram.

Computer software programmes and applications like Photoshop or Final Cut  have appropriated the visual materials traditionally related to books through their use of cut and paste, scrolls, paper clips and page turning. Digital Media theorist Lev Manovich states that ‘many new media objects are converted from various forms of old media’ (Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, 2001; p. 28). For example, a webpage can be read like a photograph album or an iPad application similar to a pack of playing cards (Manovich, p. 220). At the same time, archived text messages and emails cease to be emails. Rather they take on the form of a photograph, becoming a screen shot frame that has fleetingly captured a moment of a past life. This peculiar digital aesthetic is the essence of Spiralbound. Taking something fluid and in motion, freezing it, observing and considering it, watching it but allowing it to develop and evolve. As a result each book acts as a snapshot of live text, a fleeting moment in our spiral bound times.

have appropriated the visual materials traditionally related to books through their use of cut and paste, scrolls, paper clips and page turning. Digital Media theorist Lev Manovich states that ‘many new media objects are converted from various forms of old media’ (Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, 2001; p. 28). For example, a webpage can be read like a photograph album or an iPad application similar to a pack of playing cards (Manovich, p. 220). At the same time, archived text messages and emails cease to be emails. Rather they take on the form of a photograph, becoming a screen shot frame that has fleetingly captured a moment of a past life. This peculiar digital aesthetic is the essence of Spiralbound. Taking something fluid and in motion, freezing it, observing and considering it, watching it but allowing it to develop and evolve. As a result each book acts as a snapshot of live text, a fleeting moment in our spiral bound times.

Spiralbound books, therefore, exist in an in–between world. The books are produced and bound professionally yet they are determinedly not part of commercial publishing. These books cannot be found in bookshops. In a way they don’t really exist, as they have no ISBNS. Yet neither are they Artist Books. There may not be many copies but they are not limited editions. Print on demand allows easy access and production, and all Spiralbound books are sold at £5. They are not zines or pamphlets but borrow the DIY spirit of Punk. Just as Sluice is re-positioning and challenging the contemporary art fair, so Spiralbound, by responding to the influence of new digital technologies, is helping to re-position the Artist Book.

Spiralbound will be at Sluice Art Fair 16 – 18 October 2015

11 – 6pm

Bargehouse, Oxo Tower Wharf, South Bank

http://sluice.info/2015

To see a preview of the books at Spiralbound please visit:

http://susakpress.org/spiralbound