Over the past five years the Material Texts Network has convened a series of conferences and symposia exploring the book as a physical object. The focus of these events has been the tactility and tangibility of the page as much as its meanings, or what it is we do with books as well as (and instead of) reading them. The aim and ethos has been to transcend periodization and disciplinary specialisms, bringing scholars from diverse backgrounds together with artists, writers and cultural practitioners to discuss the nature of the material page, its possibilities and limitations, its quirks and singularities as well as its historical uses, misuses and aberrations. Since 2010 we have staged On Paper, Book Destruction, Missing Texts, and A Humument; Treatments, Reflections, Responses. The next event, Perversions of Paper, will be held in June this year.

On Paper: A Symposium Exploring the Meanings of the Material Page in the Digital Era (April 2010)

On Paper: A Symposium Exploring the Meanings of the Material Page in the Digital Era (April 2010)

Organisers: Heather Tilley and Gill Partington

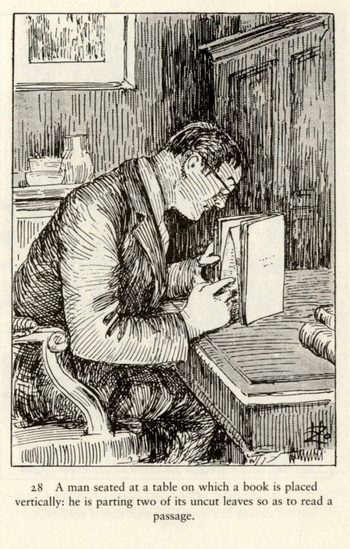

The publicity poster announced this as ‘a day of short presentations and paper fondling followed by a response by Leah Price of Harvard University’.

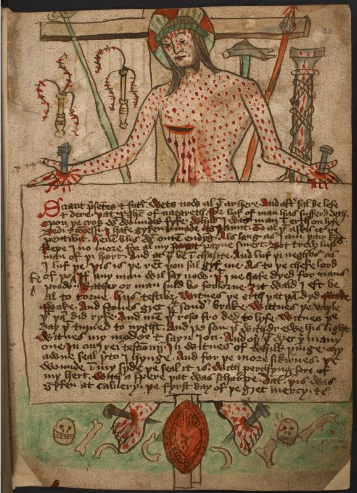

With predictable irony, Professor Price pulled out of this inaugural Material Texts Network conference at short notice, having suffered back strain lifting a suitcase full of books, but the paper fondling went ahead without her in the splendidly august surroundings of Beveridge Hall, Senate House. There were presentations about the pages of graphic novels, the fetishisation of print, medieval graffiti, Renaissance collage, nineteenth-century serials, the notebooks of Antonin Artaud and embossed books for the blind.

Papers on paper were given by Tony Venezia, Maggie Gray, Zara Dinnen, Henderson Downing, Anthony Bale, Ros Murray, Adam Smyth, and Heather Tilley. Professor Esther Leslie acted as respondent for the day, and book artist Linda Toigo presented her unique handmade, interactive edition of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. She also romped home with first prize in the lunchtime origami competition.

The conference received funding from the AHRC National Research Training scheme in Language and Literature, Palaeography and the History of the Book, and also from In the Shadow of Senate House, a research project based at Birkbeck College.

Book Destruction (April 2011)

Book Destruction (April 2011)

Organisers: Adam Smyth and Gill Partington

The destruction of the written word has huge symbolic potency, but the aim of this event was to sidestep conventional reactions in order to explore an alternative history of the book’s misuses, asking firstly about the methods and reasons for its disposal, mutilation, dismemberment and reuse, and secondly what they might reveal about our changing cultural investments in the printed page. Once again we were in the beautiful Beveridge Hall, which reverberated with shock at the opening revelation that one of the conference convenors was a known book burner, having once carelessly ignited a box of paperbacks and set fire to her own flat. The event made it into the local newspaper.

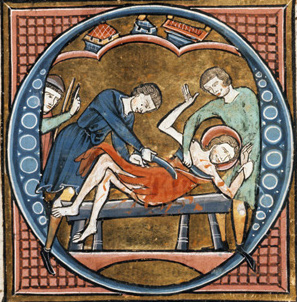

Different modes of destruction structured the day, with panels on burning, cutting, recycling and digitizing. Once again, participants were drawn from a diverse backgrounds and period specialisms, and papers ranged across such eclectic topics as Hancock’s Half Hour, George Eliot, Early Modern Broadsides, taking scissors to bibles in the Renaissance, 1970s German children’s literature, and François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451. Speakers, coming from Hawaii, Mainz and points in between were Adam Smyth, Corinna Norrick, Gabriel Egan, Brooke Palmieri, Bonnie Mak, Gill Partington, Katherine Inglis, Rebecca Knuth, Harriet Phillips and Lucy Razzall. We were also joined by two artists, Nicola Dale and Ross Birrell, who gave presentations about their uses of the book as a medium. They brought their work along to display, as did other artists, including Linda Toigo and Michael Hampton. Birrell’s looped video footage of books being destroyed with cheese graters and hacksaws made for a strangely mesmeric backdrop to the papers, and this complex relationship between destruction and artistic creation was also the central theme of the keynote address from Professor Kate Flint of UCSC, who explored the ‘altered book’ as an emerging artistic form.

The conference was developed into a collection of essays and interviews, Book Destruction in the West, from the Medieval to the Contemporary, forthcoming in 2014 with Palgrave Macmillan and edited by Adam Smyth and Gill Partington.

Missing Texts (June 2012)

Missing Texts (June 2012)

Organisers: Adam Smyth and Gill Partington

In 2012 we relocated to the Keynes Library, Gordon Square for Missing Texts, a symposium about gaps, empty spaces, erasure, ellipses and fragments. If the destruction of a book is a moment when its materiality becomes inescapable, then so, paradoxically, is the absence of text. Scholars often have to ‘read’ what isn’t there, but what can empty pages, redactions, blank spaces and torn out leaves tell us? What about the kind of texts that scholars in earlier periods routinely deal with, which simply don’t exist at all, are lost or even apocryphal, appearing only in second-hand accounts? What methods and approaches do we use in these instances?

Approaching this topic from a variety of different angles were Daniel Wakelin, Jason Scott-Warren, Heather Tilley, Caroline Archer, Karen Britland, Gill Partington, Patrick Davison, Eleanor Collins, Luisa Calé and Bethan Stevens. Topics under discussion included deleted YouTube comments, Algernon Swinburne’s censored writing, English Civil War ciphers, imagined omissions in Medieval manuscripts, and lost early modern books. Once again there was a strong emphasis on visual culture, with talks on the lost art collections of Charles I, missing paintings and the concept of ekphrasis, as well as the artist John Latham’s infamous performance of book eating.

Bookshop and exhibition space X Marks the Bokship kindly loaned us a fascinating collection of books with holes, gaps, blank pages and bits cut out. We went bowling afterwards.

The symposium became the basis for a special edition of Critical Quarterly in December 2013, edited by Adam Smyth and Gill Partington.

A Humument: Treatments, Reflections, Responses (July 2013)

A Humument: Treatments, Reflections, Responses (July 2013)

Organisers: Adam Smyth and Gill Partington

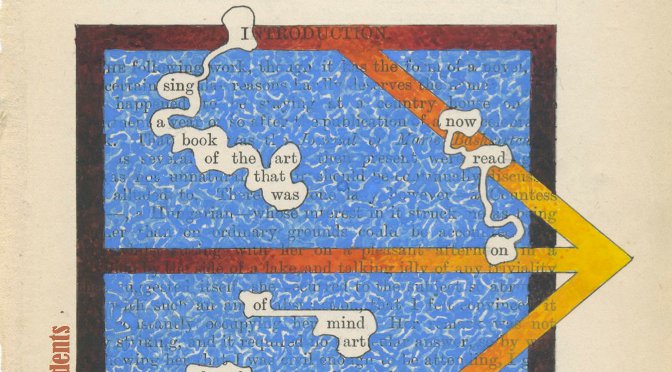

This symposium was devoted to an exploration of a single text. Tom Phillips’s A Humument is a unique work – part poem, part art object – created by overwriting, augmenting, illustrating and erasing someone else’s words. In 1966 Phillips bought a second hand copy of WH Mallock’s nineteenth-century melodrama, A Human Document, and for nearly fifty years has been working and then reworking each page. The fifth edition of this ‘treated Victorian novel’ has now been issued by Thames and Hudson, and to celebrate this event we invited Phillips himself to be our guest as we subjected it to our own reflections, responses and treatments.

Participants were Holly Pester, Gill Partington, Dennis Duncan, Tony Venezia, Zara Dinnen, Alex Latter, Adam Smyth and Luisa Calé who discussed A Humument in relation to various topics including the visual poetics of modernism, digital editions of McSweeney’s journal, experimental literature of erasure and blankness, comics, Early-Modern cut-up bible collages, and the composite page in nineteenth-century art. Phillips remained gracious and good-humoured through all of it, despite the distractions of a tense score in the Ashes Test. To close, there was a question and answer session with the writer and critic James Kidd.