A short film has been made about the rediscovery of four medieval books in the Birkbeck library.

Watch the film here:

Image credit: © 2016 Birkbeck Media Services / Dominic Mifsud

A short film has been made about the rediscovery of four medieval books in the Birkbeck library.

Watch the film here:

Image credit: © 2016 Birkbeck Media Services / Dominic Mifsud

Recently I went to my grandparents’ house (Grandpa died in 2012 and Granny lived on alone there until her own death just a few months ago) and took things from it, amongst them two large bags of books, bound by my grandfather. On first arriving at my house, these books kept themselves to themselves; but now they are mixed with the ones that Grandpa gave me in his life, amongst them A. A. Milne’s When We Were Very Young and a Complete Works of Shakespeare from 1911 which, confusingly, belonged to my other grandfather and is inscribed to him on the fly-leaf. I can remember where each of the new books was in its old place, in their house: exactly where, on exactly which shelf and in which room. They represent probably about a fifth of the whole collection. I invented some criteria and made a selection.

I say ‘took’ because it felt like taking, like theft. Can the dead be robbed? I was there in advance of an antiquarian book-dealer coming to take the remainder. And so, if it felt like theft, it also felt like abandonment; there were other orphans that I couldn’t re-home. Selection felt unkind. I once had a student (working on medieval scatology) who told me that, when his father died, his mother kept one of his father’s stools in a sample tube in her handbag for three years (is all research that autobiographical?). Somewhere between that and complete renunciation must lie a reasonable mean.

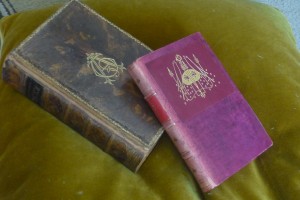

I took literary books, barring the additional copies of Jane Eyre, Bleak House and Aesop’s Fables (of course it would be those three) and then a few things from the other categories: maths and science, history and geography and one Russian book. It was the Russian book which felt most illicit; I don’t read Russian. I also took a copy of the King James Bible, a Book of Common Prayer, and Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, which goes with the Bible because Grandpa, who wasn’t a religious man (‘religion just spoils what I think’, he once said to me), used them for the cryptic crosswords. That there were definite sections in Grandpa’s library reminds me that he also had criteria when he bought the books in the first place. Not only did he buy on particular subjects, but he also said that he would never pay more than £5 for a book, wouldn’t buy one that was less than a hundred years old, or that had a perfectly decent unbroken binding already.

He didn’t stick to these criteria, though. I don’t know about the price, of course, or what they looked like before he mended them beyond my memory of the poor flapping loose quires laid out on his work bench, but there are several that aren’t a hundred yet. The newest (and so oddest) is a now a beautiful, leather-bound copy of Edgar Allen Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, which would otherwise be a rather ordinary Wordsworth Classics edition from 1995, like a thing unaccountably put into the wrong box. But there are also editions of John Galsworthy’s Forsythe Saga and A Modern Comedy, not first editions but early ones from the 1920s and 30s.  These newer books prick a memory of being a teenager and asking Grandpa to rebind a distressed copy of Tennyson’s poetry, from 1904, and feeling embarrassed. But it was nearly a hundred and he seemed to see what I saw in it, because he saved the art nouveau end papers and cut the avian cover design from the original binding and attached it to the new one. Later he gave me another, older copy of Tennyson’s verse, with a solid wood binding, mended rather than rebound.

These newer books prick a memory of being a teenager and asking Grandpa to rebind a distressed copy of Tennyson’s poetry, from 1904, and feeling embarrassed. But it was nearly a hundred and he seemed to see what I saw in it, because he saved the art nouveau end papers and cut the avian cover design from the original binding and attached it to the new one. Later he gave me another, older copy of Tennyson’s verse, with a solid wood binding, mended rather than rebound.  There are several books within the new lot that have pieces of their old binding reincorporated into the new like those editions of Tennyson: Fanny Burney’s Evelina and Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford, both have pieces of brightly-coloured washed silk over the end papers (Evelina’s is red, Cranford, yellow), although they’re not from the same series. There’s no date in either book but both, I think, are from around 1900-5. A pretty little, again undated, copy of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth retains parts of its first verdigris binding. And the one that I thought about as I was driving there to pick the books up, a 1882 copy of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, has its old gilded binding laid like lace work over the new.

There are several books within the new lot that have pieces of their old binding reincorporated into the new like those editions of Tennyson: Fanny Burney’s Evelina and Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford, both have pieces of brightly-coloured washed silk over the end papers (Evelina’s is red, Cranford, yellow), although they’re not from the same series. There’s no date in either book but both, I think, are from around 1900-5. A pretty little, again undated, copy of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth retains parts of its first verdigris binding. And the one that I thought about as I was driving there to pick the books up, a 1882 copy of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, has its old gilded binding laid like lace work over the new.

Grandpa was a physicist (he studied at Manchester under Rutherford, Bohr and Hartree); he didn’t become a book-binder until his retirement. Perhaps the majority of books were on maths and science: on logarithms, the principles of measuring, Euclid’s geometry and other things. This not being my subject particularly, I took only two from this section: Charles Darwin’s Journal of Researches and a book written for children. I had my own son in mind as its future reader: The Fairyland of Science, by Arabella Buckley (published in 1880) which has such magical chapters as ‘sunbeams and the work they do’ and a ‘history of a piece of coal’.

From the history section I took a little more, but not everything: an Atlas of Ancient Geography (1871); Frank Power’s Letters from Khartoum, Written during the Siege (1885); and a personal memoir of Tzar Nicholas I: What I Know of the Late Emperor Nicholas and his Family (1855). Which brings me back to the Russian book that I pilfered. Grandpa was a Russianist, being the only one who put his hand up when his wartime research unit were asked for volunteers to learn enough to translate Russian communiqués. ‘The New Lands’, Grandpa has helpfully embossed in English on the book’s spine and, in it, there are pictures of un-smiling, I think Siberian, people (1903). From the title and pictures I think I know what sort of book it is and I have friends and other family with Russian; so it isn’t stool- in-a-sample-tube crazy.

What else is there? Lewis Carroll; some Dickens; novels by all three Brontës; Trollope; Hardy; Austen; Eliot (George, of course, not T. S.) and Thackeray; The Diary of a Nobody; Mrs Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Bronte; a copy of Gulliver’s Travels with chromolithograph frontispieces from 1864, which must have been new and unusual; and Rider Haggard’s She with a purportedly authentic ‘facsimile’ of the ‘sherd of Amenartas’. There is a nice copy of Delamotte’s Primer of the Art of Illuminations (although a reasonably late one from the 1920s). The oldest of the lot, I think, is a two volume copy of Arabian Nights from 1813.

Amongst my favourites are four miniature books, just hand-sized nineteenth-century editions of Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield (undated); Aesop’s Fables (1854) with a long pull-out frontispiece of Aesop surrounded by the animals; St Pierre’s Paul and Virginia (1815) and Sheridan’s Dramatic Works (undated) full of fantastically opinionated remarks after each play, such as this, on Pizarro:

This far famed and popular play has enjoyed a reputation with the public, which good taste and judgment have uniformly united in decrying. As a regular drama, it is undeserving of any praise; and the pleasure with which its performance is commonly witnessed, can be ascribed only to the splendour of its scenery and decorations.

The tables had clearly turned; Julie A. Carlson describes it as the most popular play of the 1790s and the second most popular play of the eighteenth century (‘Trying Sheridan’s Pizarro’, Texas Studies in Literature 38 (1996)).

The Vicar of Wakefield has a rather formal inscription to:

Miss Gressier

A Mother’s gift

Feb 24 1849

1 Gt Charlotte St

Liverpool

Scouting around briefly on the internet I find a Jane Gressier (presumably the mother, rather than the daughter), from London House at that same Liverpool address, advertising in the Catholic Advertiser for 1840 (p. 154). There is a line drawing of London House above these words, which purports not to be an advert but evidently is:

Jane Gressier avails herself of this valuable medium to return her sincere thanks to her Catholic Friends, for the very liberal support she has received since the death of her husband, and begs to inform them that she is continuing the general Drapery Business at the above establishment, where she trusts by excellent of quality and reasonableness of Terms, to secure their future favours and recommendations.

N.B. Funerals completely furnished.

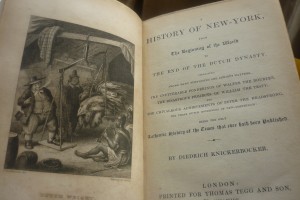

Amongst these hand-bound books I also picked up another, which is in its first binding and which Grandpa doesn’t even seem to have repaired. He must have bought it for itself. A History of New York, from Creation to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, purports to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker and, if the author sounds fantastically named, that’s because he is, being the pen-name of Irving Washington. This edition (by Thomas Tegg and Son, in London) is from 1836, although the History was first published in 1809. This is a picture of the frontispiece engraving, ‘Dutch Weight’, by Cruickshank, which depicts a fat Dutch colonist, ‘weighing’ a load of animal pelts brought to him by a native American ‘Manhatto’, which should give you a sense of the book’s satirical slant . A mock colonial history, the title page advertises the History’s bombast contents, ‘among many surprising and curious matters, the unutterable ponderings of Walter the Doubter, The Disastrous projects of William the Testy, and the Chivalrous achievements of Peter the Headstrong’.

Amongst these hand-bound books I also picked up another, which is in its first binding and which Grandpa doesn’t even seem to have repaired. He must have bought it for itself. A History of New York, from Creation to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, purports to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker and, if the author sounds fantastically named, that’s because he is, being the pen-name of Irving Washington. This edition (by Thomas Tegg and Son, in London) is from 1836, although the History was first published in 1809. This is a picture of the frontispiece engraving, ‘Dutch Weight’, by Cruickshank, which depicts a fat Dutch colonist, ‘weighing’ a load of animal pelts brought to him by a native American ‘Manhatto’, which should give you a sense of the book’s satirical slant . A mock colonial history, the title page advertises the History’s bombast contents, ‘among many surprising and curious matters, the unutterable ponderings of Walter the Doubter, The Disastrous projects of William the Testy, and the Chivalrous achievements of Peter the Headstrong’.

One of the best bits of this little volume is the ‘note on the author’ at the front which tells the story of Knickerbocker’s going missing from his hotel accommodation without settling the bill. When the landlord of the hotel, Seth Handaside, breaks into his room he finds the manuscript of his History, which he publishes to recoup his costs. Jerome J. McGann relates how Washington drummed up interest in his fabricated author, in advance of the History’s publication:

In October and November [1809], Irving wrote and planted in the newspapers a series of hoaxing press notices. These introduce the reader to the ‘mysterious disappearance’ of ‘a small elderly gentleman’ from the ‘Columbian Hotel’ in New York. The gentleman is subsequently revealed as a Mr. Diedrich Knickerbocker, and we learn that he left behind in his hotel room ‘a very curious kind of written book. . . in his own handwriting.’ The imaginary landlord of the imaginary hotel, Seth Handaside, informs the public that he intends to ‘dispose of [the] book’ in order to ‘satisfy’ Knickerbocker’s unpaid bill. And so it comes to pass that A History of New York is published in early December 1809 in two volumes by Inskeep and Bradford.

~ ‘Washington Irving, A History of New York, and American History’, Early American Literature 47 (2012): p. 350.

This is all, obviously, completely wonderful in itself. Yet, on top of that, the inscriptions in the front of the History tell of the book’s interesting journey to my shelf. An inscription in the book indicates that it was in Leeds, the property of a Louis Taylor in 1857 but, in the First World War, it ends up, we know from stamps on the endpapers, in the War Library of the British Red Cross, in the recreation hut of No. 7 convalescent depot in Boulogne. There are some photographs taken by the war photographer Tom Aitken of one of these recreation huts and of men reading in it. I look at these photographs and hope to see A History of New York if I look closely enough, but can’t. These were camps for the recovering wounded, on their way back to the front; I wonder what they made of the Knickerbocker History. Then somehow it got itself to Grandpa’s shelf and now it is here.

I look at these photographs and hope to see A History of New York if I look closely enough, but can’t. These were camps for the recovering wounded, on their way back to the front; I wonder what they made of the Knickerbocker History. Then somehow it got itself to Grandpa’s shelf and now it is here.

The first 40 of Grandpa’s other books, the maths and science ones that I left behind on his shelves, have just gone on sale at Portman rare bookshop in Tonbridge. I almost didn’t take, but at the last minute phoned my mother, tired from a night going over all the others I’d left, too, and asked her to also put the five volumes of Boswell’s Life of Johnson to one side. The ones I didn’t save will be up for sale soon: the books about Lancashire, where grandpa was born in 1916 and brought up; those alternative copies I mentioned and many others that I now can’t remember. Even as I put in this hyperlink I know that it is temporary, a virtual connection to dwindling stock that will one day bring up other books, bound by others, as well or instead of his. If you buy one, let me know so I can know it’s on your shelf.

I also took with me four boxes of embossing tools: a complete set of upper case and lower case letterpresses, full punctuation and numbers sets, plus fleur-de-lis and foliage presses. I remember using these as a child; my sister and I pressing our names into off-cuts to make bespoke bookmarks and labels for personalized boxes and notebooks. And when my son is old enough perhaps he will press his own name into a piece of leather and keep it warm in his pocket like a treasure; and maybe I will bind books in my retirement and keep these tools with jars of amber glue-beads and felt-lined vices, like Grandpa did.

I also took with me four boxes of embossing tools: a complete set of upper case and lower case letterpresses, full punctuation and numbers sets, plus fleur-de-lis and foliage presses. I remember using these as a child; my sister and I pressing our names into off-cuts to make bespoke bookmarks and labels for personalized boxes and notebooks. And when my son is old enough perhaps he will press his own name into a piece of leather and keep it warm in his pocket like a treasure; and maybe I will bind books in my retirement and keep these tools with jars of amber glue-beads and felt-lined vices, like Grandpa did.

As I drove away with my stolen property, I wondered about my own materiality, my need to keep and own these lovely things. Characters in books who, one way or another, survive their own deaths, often look down and laugh at that need, at our connection to things, our silly unspiritual side. Because, for the dead, things literally don’t matter anymore. And I thought about Grandpa up ‘there’ (in the eighth sphere or wherever else the dead go) looking down and, although he had a childlike sense of humour in life, I couldn’t bring myself to imagine him laughing. Instead, I could very clearly hear him saying: ‘you are absolutely right, Isabel; it is the books: the books are what life is really all about’.

Medieval pictures which depict flaying or flayed people are usually full of draped fabric, suggesting an association between skin and clothing so common as to be very easily evoked. Sarah Kay (JMEMS, 2006) has investigated the changing representation of St Bartholomew (who was martyred by being skinned alive), which suggests that the association between clothing and skin was central to his medieval but not his later manifestations. In the Early Modern period St Bartholomew became an échorché, carrying his own skin as in this mid-sixteenth-century Italian sculpture.

Medieval pictures which depict flaying or flayed people are usually full of draped fabric, suggesting an association between skin and clothing so common as to be very easily evoked. Sarah Kay (JMEMS, 2006) has investigated the changing representation of St Bartholomew (who was martyred by being skinned alive), which suggests that the association between clothing and skin was central to his medieval but not his later manifestations. In the Early Modern period St Bartholomew became an échorché, carrying his own skin as in this mid-sixteenth-century Italian sculpture.

In contrast, in medieval iconography, whilst he regularly carries his symbol – a flaying knife – and sometimes also his own skin, he is usually depicted before his flaying, with his skin still intact and dressed in heavily draped clothing.

In contrast, in medieval iconography, whilst he regularly carries his symbol – a flaying knife – and sometimes also his own skin, he is usually depicted before his flaying, with his skin still intact and dressed in heavily draped clothing.

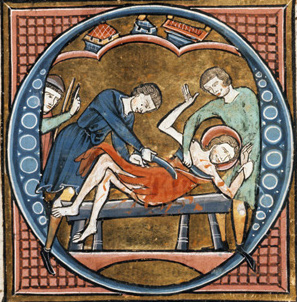

In some other medieval depictions his bloodied skin is made to look like worn clothing, as in this illumination from a thirteenth-century book of French saints’ lives. St Bartholomew’s clothes, and then his skin, came off in the sixteenth century. Michelangelo’s famous depiction of the saint in his Last Judgement fresco in the Sistine Chapel represents a ‘half way house’ in which the saint wears no clothes (the drape of fabric he now wears was added later on the orders of the Council of Trent) but simultaneously carries and wears his own skin.

In some other medieval depictions his bloodied skin is made to look like worn clothing, as in this illumination from a thirteenth-century book of French saints’ lives. St Bartholomew’s clothes, and then his skin, came off in the sixteenth century. Michelangelo’s famous depiction of the saint in his Last Judgement fresco in the Sistine Chapel represents a ‘half way house’ in which the saint wears no clothes (the drape of fabric he now wears was added later on the orders of the Council of Trent) but simultaneously carries and wears his own skin.

With the Early Modern divestment of St Bartholomew goes the ready substitution of skin and clothing. People’s proximity to industrial processes no doubt forged this earlier connectivity; there was a reflex understanding of the ‘before’ and ‘after’ states of animal products which made them into substitutes in medieval art and literature. ‘I wolde be clad in Cristes skyn’, wrote an anonymous medieval lyric-writer: gruesome clothes indeed.

With the Early Modern divestment of St Bartholomew goes the ready substitution of skin and clothing. People’s proximity to industrial processes no doubt forged this earlier connectivity; there was a reflex understanding of the ‘before’ and ‘after’ states of animal products which made them into substitutes in medieval art and literature. ‘I wolde be clad in Cristes skyn’, wrote an anonymous medieval lyric-writer: gruesome clothes indeed.

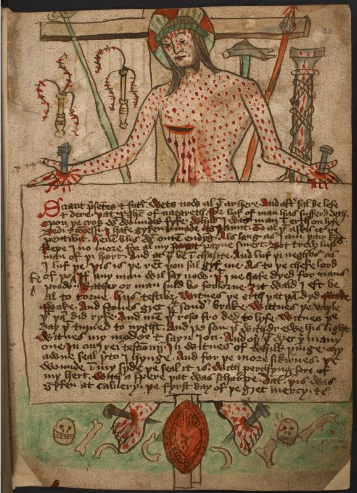

Yet, as Sarah Kay reminds us, Bartholomew is the patron saint of parchment makers as well as leather workers, and a similar proximity between skin and parchment offered another set of prefabricated metaphors for medieval poets. The so-called ‘Charters of Christ’, a set of related late-medieval poems in which Christ makes a charter with mankind, are at the centre of a tradition of affective poetry which exploit the relationship between skin and parchment for Eucharistic meditation.  In the long version of these poems, Christ (who is understood in scriptural metaphor as a kind of sheep, the lamb of God or agnus dei), having no parchment on which to write his charter, writes it on his own skin, using one of the instruments of his passion as a stylus. The ink is sometimes made of his blood and sometimes, anti-Semitically, of Jews’ spit; the charter is sealed with wax made from his heart. The description of the crucifixion itself – Christ’s scourging, stretching and drying – is also a recipe for making parchment and deploys the trade vocabulary of the parchmentiers. This long version of the poem survives in fourteen manuscripts, however its analogies were well enough known by readers of other medieval texts, that they could be fairly lightly referred to and yet the whole tradition evoked. So, for example, in the Short Charters the words of the charter are typically presented without the contextualizing narrative about Christ’s bodily substitutions for writing materials and yet the images which sometimes accompany them visually cite them.

In the long version of these poems, Christ (who is understood in scriptural metaphor as a kind of sheep, the lamb of God or agnus dei), having no parchment on which to write his charter, writes it on his own skin, using one of the instruments of his passion as a stylus. The ink is sometimes made of his blood and sometimes, anti-Semitically, of Jews’ spit; the charter is sealed with wax made from his heart. The description of the crucifixion itself – Christ’s scourging, stretching and drying – is also a recipe for making parchment and deploys the trade vocabulary of the parchmentiers. This long version of the poem survives in fourteen manuscripts, however its analogies were well enough known by readers of other medieval texts, that they could be fairly lightly referred to and yet the whole tradition evoked. So, for example, in the Short Charters the words of the charter are typically presented without the contextualizing narrative about Christ’s bodily substitutions for writing materials and yet the images which sometimes accompany them visually cite them.

This is true, for example, in the York Pinners’ Play, the part of the York cycle drama which depicts the crucifixion. In that play the soldiers who crucify Christ are depicted as labourers and the crucifixion is part of their everyday work, which they go about with little grace and much complaint about its arduousness. In their grumbling banter they place a special emphasis upon the effort of stretching Christ: ‘tugge’ and ‘[l]ugge’ they urge each other. Pinners, of course, made nails (‘nayles large and lange’, is how they are advertised in the play) and, although in the drama they are used to crucify, in medieval industry they were more typically used, amongst other things, for fastening skins to tenters (special stretching frames) to make cloth and parchment. When, late on the play, Christ finally speaks he does so in terms which are reminiscent of the parchment-Christs of the Charters, citing the same Biblical text (Lamentations 1.12) which also features prominently in the Charter poems. Like the Charter Christs, Christ in the Pinners’ Play asks for the audience’s attention: ‘take tent’, he commands. The Middle English word ‘tent’ is an aphetic form of ‘attent’, a cognate of modern English ‘attention’ and ‘attend’. Whereas modern English has forgotten the mechanical image in these words, medieval people would have associated them with the idea of stretching (the word comes from Latin adtendere, to stretch) and, like ‘nayles’, ‘tent’ would have been a common word in the pinners’ trade lexicon. Thus Christ asks the play-goers for their stretched attention; he asks them to imitate him, stretched out like parchment to dry on a frame.

When one starts to look, the imagery of stretched parchment occurs regularly in Eucharistic contexts. A weird little late-medieval story, that turns up in a number of places and is embedded for instance in a poem which explains ‘How to Hear Mass’, describes the way that the devil eavesdrops on, and writes down the chit-chat of women in church. He writes so much that he runs out of parchment and, whilst trying to stretch it further, snaps it, causing his head to smash into a pillar. Whilst lots of critics have discussed the way in which the story warns women against speaking in church, deploying a standard misogynist trope which is regularly seen elsewhere, for me, if this is all this story were, it oddly doesn’t work in the way that one might expect. The women aren’t punished; indeed, because they talk a lot the devil is more injured. St Augustine, who is giving the sermon in the story, and Pope Gregory, who has commissioned it, laugh to see the devil so confounded. The story is already set during the Mass and this, along with a medieval reader’s recognition of parchment as a figure for the body of Christ, suggests an allegorical reading, which is not often how it is treated in the modern critical literature.

In another example, when Thomas Hoccleve complains about the sufferings of writers, that their work is laborious ‘elengere’, that they must endure (‘dryen’) eye-strain, when they pore over the ‘shepes-skyn’, it is hard not to recall the metaphorical fields that I have limned out above. Hoccleve implies, without fully saying, that he has ‘taken tent’ of Christ’s commands and imitates his suffering in the physical act of writing. Hoccleve tells us, in another piece of his life-writing, that he once borrowed a book with which he intimately identified, which seemed to describe the very workings of his being but, then, before he had finished or properly remembered it, had to return it. It is appropriate that this patchily read and remembered book is the model for his account of his erstwhile madness, in which (as he says): ‘the substance of my memorie / wente to pleye as for a certain space’. Books cover Hoccleve in a surprisingly material way: so that his absences and presences of mind depend on the vagaries of the physical circulation of particular manuscript books.

The material nature of parchment, then, was crucial for the way that medieval people read and wrote. Its animal nature meant that it was already metaphorical, even before it was written on. We might ask, because these Christological associations are so ubiquitous, whether medieval people could ever read, or write on parchment without them in mind. Today we are used to thinking about text in a somewhat unlocated way: we might read a text in this edition or in that one, electronically or in hard-copy; for medieval readers, however, the text was much more ‘locked down’ to particular pages, in particular books. Indeed, Mary Carruthers has shown that the sophisticated memory technologies of the Middle Ages relied extensively on people’s recall of particular pages and how they were laid out. Medieval people understood their books and pages to be material, not just in the sense of being tangible, but also of previously having had different raw states, states which suggested a cluster of metaphors for the acts of writing and reading. In contrast today we don’t tend to think much about the wood pulp or computer codes that have made up our ‘books’, and those raw materials figure very little in the metaphorical planes of their contents. I wonder what those contents would look like and what effect they might have on us as readers if they did?

For a longer discussion of these ideas and a fuller bibliography, see Isabel Davis, ‘Cutaneous Time in the Late Medieval Literary Imagination’, in Katie L. Walter ed., Reading Skin in Medieval Literature and Culture.

Birkbeck College is running evening tuition in masters-level modules which will be open to all students with a good undergraduate subject in a related discipline.

In October 2014 we will be offering a 9 week module (one evening a week) on ‘Medieval Text and Intertext’ and in October 2015, a module on ‘Medieval Material Texts’.

Medieval Text and Intertext will consider medieval texts in their interdisciplinary contexts. Students will look at issues of genre, form and literary theory in the texts of a manuscript age. The course will be taught through case studies, investigating some of the most spectacular works of the English Middle Ages. Medieval Material Texts considers medieval manuscripts in their literary contexts. Focusing particularly on English medieval texts, this course considers the relationships between the physical format of manuscripts and their curious contents.

At the end of each course students will have the opportunity to write an independent research essay under academic supervision.

Birkbeck is a great place to come and try out material text or medieval studies. We are located in the midst of some of the best research libraries and resources in the world. We have research-active staff with leading publication profiles. There are lots of other optional interesting events in which to take part.

For more information about this course contact: Dr Isabel Davis (i.davis@bbk.ac.uk).