Animation artist Shay Hamias and Birkbeck academic Professor Anthony Bale have been awarded funding by the Leverhulme Trust for a ten-month residency by the artist, to be based in Birkbeck’s School of Arts. Their project will explore medieval manuscripts as a source, inspiration, and critical intertext for contemporary animation.

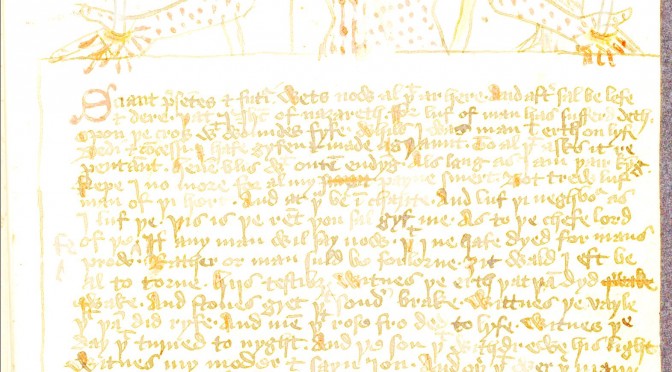

The project takes as its cue the idea that illustrated manuscripts sought to ‘animate the letter’ – that is, to bring the word to life through visual and media effects. Working with the medieval manuscript holdings of Birkbeck’s library and of other London institutions, Hamias will explore what animation can bring to the vibrant, lively world of the medieval page.

Hamias and Bale are both interested in questions relating to design, ways of reading, and the status of media. Can animation help us see what we can no longer see in medieval books? Can we activate the emotions of a contemporary viewer in similar ways to how our medieval predecessors responded to the illuminated manuscript? What techniques did medieval artists use to animate the mind and communicate via the eyes? What techniques and illusions were used to evoke visual or intellectual ‘movement’? Might animation offer a translation of a medieval mode of viewing, one which is more comprehensible to the modern viewer but based on medieval imagery?

The main outcomes will be

- the development of an entirely new interface between contemporary animation and medieval studies

- a mutually-creative encounter, with impacts through Birkbeck including its Library, including public and scholarly symposia and new animated films by Hamias. Hamias is particularly interested in animating a contemporary counterpart to the medieval book that would expand on the visual language of the Middle Ages to address a present-day issue or narrative.

- resources for further work on animation and medieval manuscripts, which will include Hamias’ films as creative responses to a range of medieval manuscripts, including those held by Birkbeck.

Shay Hamias will take up his residency at Birkbeck in January 2017. For examples of his work click here.

For more details about the Leverhulme Artist-in-Residence scheme click here

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy our previous posts about the Birkbeck manuscript and rare books collection here and here.