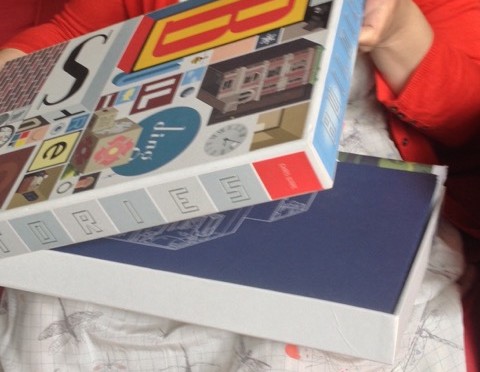

Chris Ware, Building Stories (London: Jonathan Cape, 2012). A piece of work produced as part of The Book Unbound module at Birkbeck run by Dr Luisa Calé.

Chris Ware’s Building Stories (2012) is a graphic novel presented and sold in a box. Following in the footsteps of Marc Saporta’s Composition No.1 (1961), B.S Johnson’s The Unfortunates (1969) and Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch (1966) Ware’s Building Stories is an example of a contemporary novel that subverts the materiality of the book. The box is 42cm in length x 29cm wide x 4.5cm deep and has the appearance of a board game. Martha Kuhlman has suggested that the design of the box creates a parallel with French avant-garde comics group ‘Oubapo’ which means ‘workshop of potential comics’; she writes, ‘[f]or Ware and the French cartoonists, comics become a kind of game in which one can manipulate and test the limits of the medium’ (The Comics Journal, 8th October 2014). In Ware’s Building Stories the game we are being asked to play concerns the anxiety of story making itself. It demands the reader’s participation, forcing us to build the stories physically. Visually it re-creates childhood memories of playing board games yet this is a game we play on our own. On the base of the box a diagram instructs the reader to open the lid and further separate its contents by depositing the materials in specific locations such as the kitchen drawer, the bookshelf or underneath a table. This diagram serves as a clue to one of the book’s central themes: our relationship with buildings especially the family home.

Inside the box are fourteen different pieces (tabloids, pamphlets, comic books, booklets, flip books, a poster, two hardcover books and accordion book). This generous wealth of materials immediately recreates the essence of Sunday newspapers, with their numerous sections, advertising leaflets and supplement magazines. The box’s contents consist of stories recalling the loss of romance, sex, childhood, virginity, home equity, ambition, creativity and the lost dream of being an artist. Seen mostly through the eyes of Ware’s female protagonist, we witness the loss of family members, friends and pets (her Dad, Stephanie and the cat), the loss of relationships and friendships (her first boyfriend the life model and her friendship with Stephanie) and even the loss of her leg (through a childhood accident). By physically scattering these materials of individual loss out of the box we re-enact the characters’ pain and re-make the book as performance.

Within the loose layers of Building Stories are two bound hardback books. Both books engage with the idea of the book as a private and personal object. Through its dimensions and gold leaf spine, the smaller book replicates in appearance the Little Golden Book Series so evocative of American childhoods. Inside the front cover is a pattern of leafy vines, flowers, animals and a space for the reader to sign their name as if it were a child’s diary. This design challenges notions that comics are for children only. The sense of diary adds a visual outer layer to the theme inside, which is a story of three different lives acted out within 24 hours. It is the only material that is dated (23rd September 2000) within the box and each page is represented by one hour through the numbers of a clock, starting at 12am and finishing at 11pm. The final page is dated April 20th 2005, 3pm and shows a young woman returning in a car with a baby to the house where she once lived, which is now for sale. The other hardback looks and feels like either an artist’s sketchbook or a banking clerk’s accounts ledger. It is A4 size, has a beige cloth binding and a sea green colouring. The secrecy (there is no information anywhere on the cover) engineered through its appearance symbolises the account or portrait of the young woman’s life: she remains unnamed throughout the collection of materials.

The accordion book is the material most like an object, and can work as an object on permanent display exhibited out of the box like a sculpture, rather like John Baldessari’s Artist Book The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1988) displayed at museums such as MOMA (New York) and the Victoria and Albert (London). Unfolded and free standing Building Stories can be read like a surgical screen. On the front are stories and clues about the house. It works almost as a pop-up theatre, a backdrop to the layers of other materials. The pages are not separate; rather, they connect into one another and therefore can be read as interlocking sequences or as a whole image, like a cinema screen. The diagrams on the reverse side work like mind maps to the internal prisons of the house. If the reader interacts with the accordion (and pushes the walls in) it becomes like the house itself, an upright 3-dimensional rectangle with four enclosing walls, an inverted house where the images and story and characters lives are on the inside.

The images of characters reading iPads, iPhones and iMacs throughout Building Stories show Ware engaging with the contemporary culture of consumer digital technology within relationships. In the ‘Disconnect/ Browsing’ booklet, presented in A4 comic strip format, Ware draws images of couples in bed, with a glass of wine, at meal times, in the supermarket, always with a tablet or smartphone in hand. The screens are drawn blank and therefore become portraits (shiny blank computer screens reflect and act as mirrors). These representations of shiny, expensive objects are in stark contrast to the raw materials of the codex format in which the novel is presented. Yet within the comic’s panels the images of the different rooms in the house reveal no books. It is as if books no longer exist. Is Ware warning that books and print are no longer relevant and are being replaced by digital tablets? The only time the female narrator picks up a book she describes it as a dream. Ware is thus contrasting the cold material of technology with other? materials rich in texture and physicality. Within these physical, sculptural forms he draws the clinical, cruel image of a naked man on bed glaring at an empty screen as his partner look on, naked, clothes stripped to her feet. This image is what Ware has done to the materiality of the book: undressed, shredded and stripped of its bindings to a raw, naked, dis-connected self.

The ‘Browsing’ booklet shows the unnamed woman dreaming of being surrounded by books. We know it is set in the future because her daughter is a grown woman and her husband the architect is referred to in the past. Drawn through twelve square panels she is pictured walking amongst shelves of books with the line: ‘One of those big chain bookstores that don’t exist anymore’. There is a sense that books and bookshops no longer exist, replaced by our ‘browsing’ of digital technologies. Ware draws her bending down, rummaging through a bright red box on a grey floor.

‘And it wasn’t…I dunno…it wasn’t really a book, either…it was in…pieces, like…Books falling apart out of a carton…’

The box of Building Stories and its loose materials is therefore involved in the text. Yet it is depicted as a dream. A fantasy image of loose liberated sheets of writing materials falling into space surrounded and watched by the packed shelves of a forgotten bookstore.

Chris Ware’s Building Stories is a contemporary graphic novel that subverts the materiality of the book. Ware achieves this aim by gathering the raw materials of the codex and presenting these materials as unbound layers in a cardboard box. As a consequence his material has a non-linear narrative and embraces a discontinuous reading. Through the nature of its physicality it challenges the reader to participate with the book’s materiality. By doing so the reader, through an act of performance disguised as reading, mirrors the book’s theme of characters connecting and dis-connecting, of human isolation, and material and physical loss.

Ware is also a rare example of a contemporary artist who uses the medium of the newspaper as an outlet for his work. The materials of Building Stories have appeared scattered in newspapers and magazines such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian and The Chicago Reader long before the ‘Box Set’ of Building Stories was published in 2012. His latest work The Last Saturday has appeared every Friday since September 2014 solely for The Guardian website. This on-going project can be read as a sign of Ware’s growing engagement with the materiality of new digital technologies (as seen in Building Stories). By continuing his subversion of the book form on a digital media platform, Ware is connecting to a global audience, creating new forms of readership.

are interested in book-collecting – whether it’s rare books, comics, or classic Penguins – to meet up with like-minded people. Meetings and visits will be held throughout the academic year and the full programme of events will be announced shortly.

are interested in book-collecting – whether it’s rare books, comics, or classic Penguins – to meet up with like-minded people. Meetings and visits will be held throughout the academic year and the full programme of events will be announced shortly.

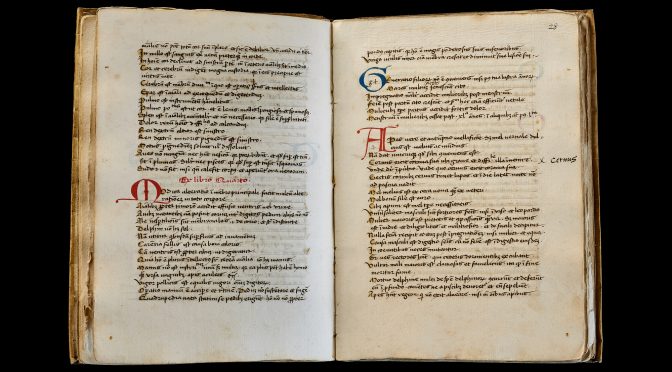

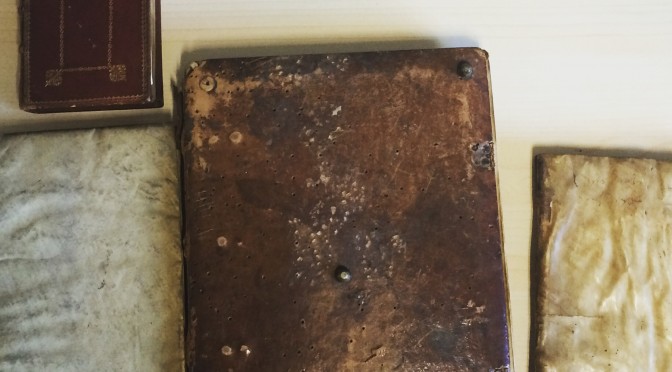

!['Philosophia Naturalis, Compendium Clarissimi Philosophi Pauli Veneti' Paul of Venice Paris: J. Lambert, [ca. 1515?] M [Paulus] SR](http://www.materialtexts.bbk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Chaucer-exhib-2015-Paulus-Venetus1-209x300.jpg)