It will, of course, be no surprise to textual scholars and members of the Material Texts Network that textual variance is rife in works of contemporary fiction. However, for a number of reasons – pertaining to copyright, digitisation, and an assumption among many hermeneutic/theoretical critics that texts published around the world are self-identical – textual variance remains an under-studied phenomenon for those working on novels that are fresh off the (digital) press.

When I was recently working on David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas [2004], however, I found a range of variants that exceeded my usual expectations of accidentals by quite some range. One of the chapters (‘An Orison of Sonmi ~451’) was almost totally rewritten in US and electronic editions of the text. I decided to investigate this further, even wondering whether the author had deliberately submitted different manuscripts to different publishers in an attempt to play a trans-textual game (the chapter in question does, after all, focus on storing the words of a death-penalty convict within a state archive for preservation and stability).

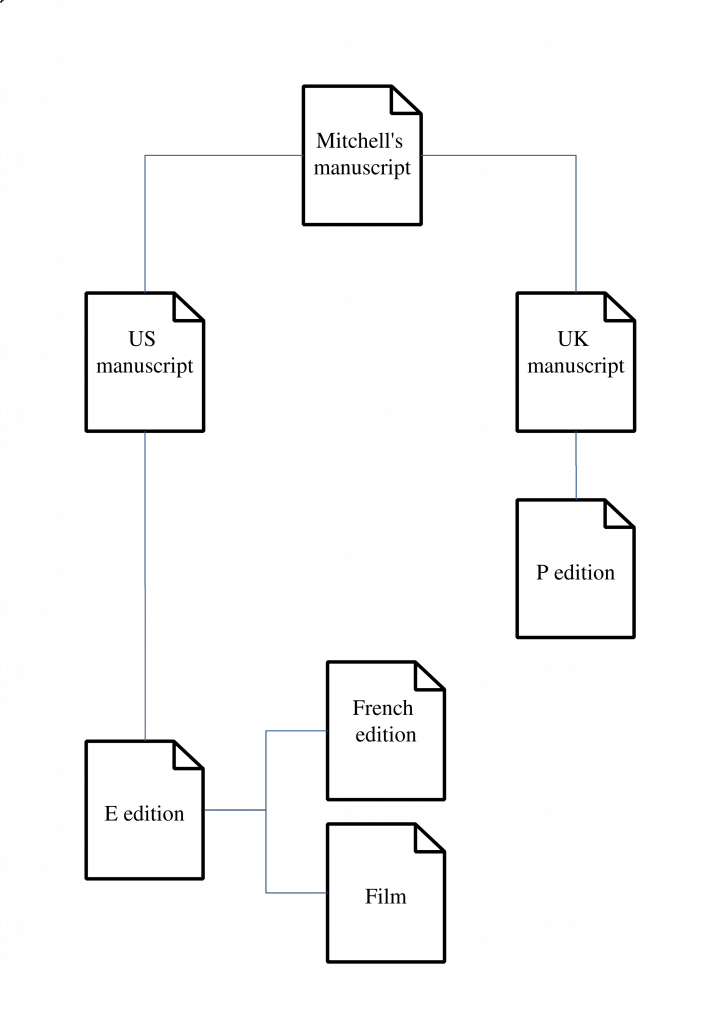

It turns out, as ever, that the differences are due to a social flaw in the editing process and not due to any technological aspect. Indeed, in 2003, David Mitchell’s editorial contact at the US branch of Random House moved from the publisher, leaving the American edition of Cloud Atlas without an editor for approximately three months. Meanwhile, the UK edition of the manuscript was undergoing a series of editorial changes and rewrites that were never synchronised back into the US edition of the text. When the process was resumed at Random House under the editorial guidance of David Ebershoff, changes from New York were likewise not imported back into the UK edition. In the section entitled ‘An Orison of Sonmi~451’ these desynchronised rewritings are nearly total at the level of linguistic expression between UK and US paperbacks/electronic editions and there are a range of sub-episodes that only feature in one or other of the published editions.

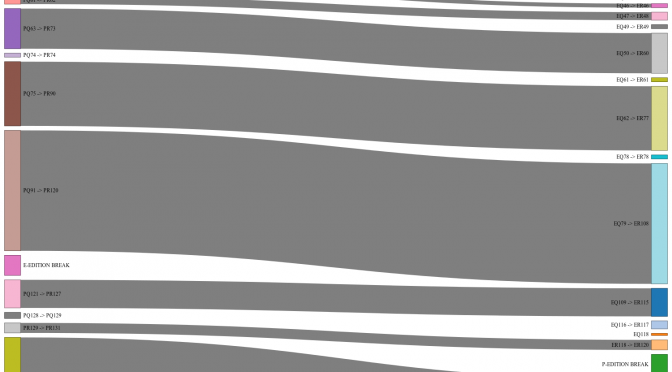

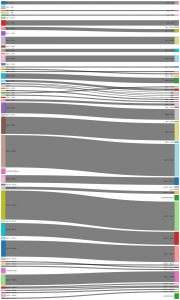

What I really wanted to know here, though, was what these edits actually did to the text. How would close reading be affected by these changes? What was actually different, and where? Since the extent of linguistic changes would be drastic, I compared functional questions and responses in this chapter (which takes the form of an interview). In other words, if, in terms of plot development, a Q&A was doing the same job in both editions, then I marked the sections as identical. I then modified the D3.js Sankey chart software to allow unlinked nodes and… hey presto, we can roughly visualize the changes to the syuzhet introduced through the editorial process.

Reading from top to bottom of this diagram on both sides allows us to see clearly reorderings and omissions between editions.

But… so what? “We” know that texts vary and that this is likely to be the case in the contemporary as much as in medieval studies. But that’s not the case for everyone. Indeed, as James F. English has noted, the canon of contemporary fiction in the academy is broadly determined by the literary prize culture circuit. Yet, with such variance, who can even be sure that all members of an international jury are reading the same text? What about online international book groups? What about local book groups where some readers are using a digital edition? What about the mass of academic criticism that has conducted close reading of one or other versions but never noticed these differences?

So much for close reading…

The full version of the article is available to read at: Eve, Martin Paul, ‘“You Have to Keep Track of Your Changes”: The Version Variants and Publishing History of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas’, Open Library of Humanities, 2 (2016) <http://dx.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/olh.82>